What does experiencing a northern fjord or a southern temple mean to us? Do we feel touched if we face Mona Lisa in the Louvre, or if we pass a line on the ground that marks the former Berlin Wall? And do we become more mindful if we taste grandmother’s favourite dish or try an old recipe shared with us by the migrants next door?

Interpretation means to add meaning to experiences, whether this comes from feelings or thoughts. How we interpret heritage is critical for the way we shape our common future.

Heritage interpretation is deeply rooted in human culture. Even the decision to keep something as an inheritance requires an act of interpretation. In the old days, shamans and priests were considered professional interpreters, and following the Age of Enlightenment, European philosophers developed their own ideas of how heritage might be interpreted.

However, the first seminal book on ‘Interpreting our heritage’ was written in 1957 for the US National Park Service. Its author, Freeman Tilden, defined heritage interpretation as:

an educational activity which aims to reveal meanings and relationships through the use of original objects, by firsthand experience, and by illustrative media, rather than simply to communicate factual information.

In his book Interpreting our Heritage, Freeman Tilden sets this definition in the context of the over-riding aim of revealing the significance of a site to non-expert visitors.

Since Tilden’s book was published, others have refined his definition in different ways, but his key principles are still widely adopted.

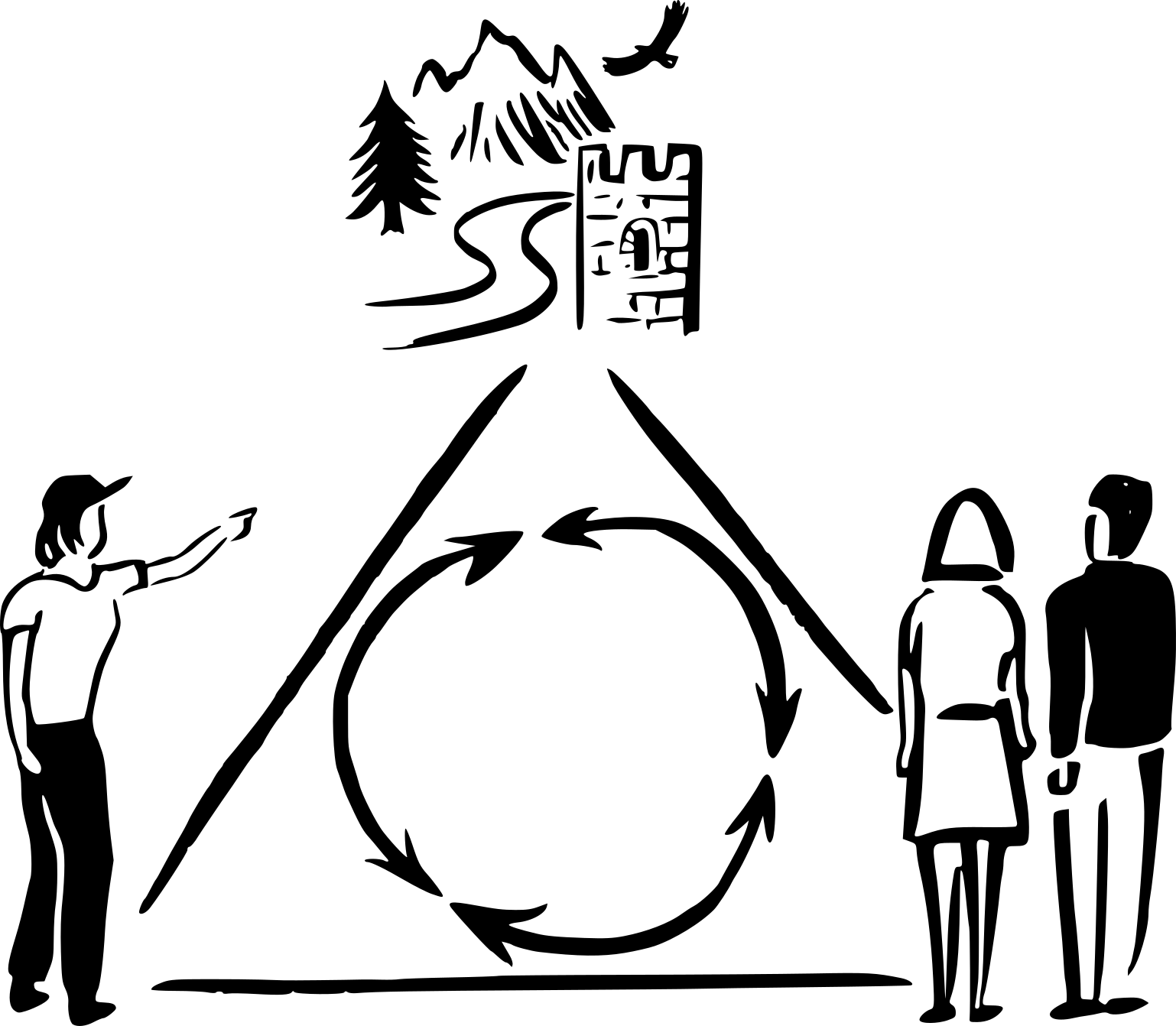

Today, we engage and empower people to interpret on their own by:

- Offering paths to deeper meaning;

- Turning phenomena into experiences;

- Provoking resonance and participation;

- Fostering stewardship for all heritage.

Professional interpreters do not only facilitate learning processes as guides in face-to-face dialogues. They also make use of other media supporting the experience of heritage, including audio guides, text panels, multimedia apps etc. They provoke peoples’ curiosity and interest by relating the site or objects to the participants’ own knowledge, experience, background and values. Professional interpreters also refrain from simply communicating unrelated facts or strictly defined messages.

The principles of heritage interpretation are used within local communities but even more to involve visitors at protected areas, monuments, museums, zoos, botanical gardens, and many other places where heritage can be experienced.

Heritage interpretation is distributed worldwide. It is based on considerable research and taught at all levels from vocational training to university degree.