An exhibition celebrating culture, community and resilience.

Diversity is now a basic characteristic of the western world, reflected in growing racial, ethnic and cultural differences across populations. For example, it is estimated that, by 2050, some 30% of the UK population will be from minority communities.

How nation states incorporate this diversity is one of the great challenges of our age. It has major implications for museums, heritage sites and cultural institutions – access and participation by marginalised and minority groups has become a strategic objective of governmental arts and cultural policies. But access and participation are not enough. Incorporating diversity also requires representation and recognition of both community contributions to wider society and the expertise migrant communities can offer. The Rebuilding Lives temporary exhibition at Leicester Museum and Art Gallery demonstrated what could be achieved.

Leicester was the first city in Europe where the majority of its population came from minority communities. Ugandan Asians, one of those communities, were people of Indian descent who settled in Uganda when it was a British Colony. Despite their small numbers, they came to dominate the Ugandan economy – resented by native Ugandans. In 1972, the then President, Idi Amin, ordered them to leave within 90 days. They could take £55 per family plus a suitcase each. Over 60,000 people had to flee, leaving behind their money, homes, businesses and way of life. Some 27,000 came to the UK. Around 10,000 settled in Leicester, despite strong opposition and racism there. Most arrived homeless, jobless and penniless – but determined to rebuild their lives.

With 2022 marking the 50th anniversary of their expulsion, there was strong community demand in Leicester for a commemorative exhibition. Navrang Arts, a local Indian Community Arts organisation, negotiated a prominent gallery space in Leicester Museum & Art Gallery, established a volunteer team, including myself, and successfully applied for funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

The entire exhibition was based on the lived experiences of those involved – oral histories and memories triggered by photographs, archive film, family cinefilms and objects they had brought from Uganda. The central themes of the oral histories (recorded by trained volunteers) provided the main exhibition themes. At ‘Memory Days’, held in community venues to gather material for display, people brought along their items and talked about why they were important. These conversations became object labels and image captions. Having talked with us, the people at the memory days then chatted with each other – so these days became celebrations in their own right.

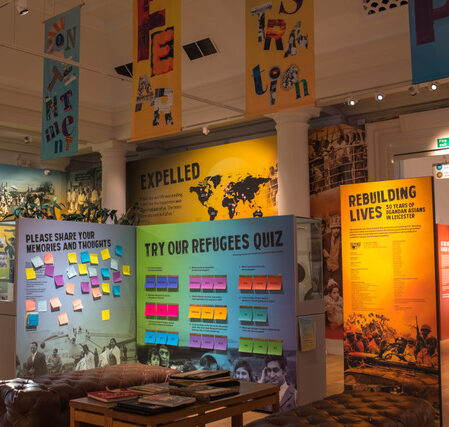

We wanted exhibition visitors to immerse themselves in the exhibition. Using the height of the gallery space, we digitally printed vinyl wallpaper for our graphics and had local students produce banners. Colour and a soundscape added to the sense of occasion. A ‘Reflection Zone’ encouraged visitors to contribute their own memories and thoughts, which then became part of the exhibition. Many stories were told and tears shed. Hundreds of post-it notes contributed people’s thoughts.

The focus of the exhibition was not on the Ugandan Asians as victims of Amin – rather, it celebrated community achievements since their arrival in Leicester. The community also ensured that part of the exhibition looked at the plight of contemporary refugees, feeling a close kinship to them.

The final exhibition was described by one seasoned museum professional in these words:

The Rebuilding Lives exhibition is superb – truthful, engaging, emotive, and full of people celebrating life.

More than 100,000 people visited – a large number for a community exhibition in the UK, let alone one in a relatively small city. Many were Ugandan Asians and their families, travelling long distances to visit. But the overall audience crossed racial and ethnic boundaries – and temporarily transformed the demographic make-up of users of the museum. And the project spread – eventually including four exhibitions in other towns and cities, over 90 events and a full schools’ programme

The Ugandan Asian community were really proud of what we achieved. But, despite its success in showing the potential for community engagement, it is a one-off. The gallery space has been given over to contemporary art. This is phenomenally depressing. Museums must change or they are going to find themselves catering to smaller and smaller segments of the overall population.

Nevertheless, we are immensely proud that the exhibition has been shortlisted for a Museums and Heritage Award 2023 in the category of ‘Best temporary or touring exhibition of the year’. I will be talking about the exhibition within my keynote paper at iecon23 in Romania and we hope to know by then whether this exhibition was the winner of that award.

Graham Black is Emeritus Professor of Museum Development at Nottingham Trent University, UK. He has worked in and with museums for over 40 years. His fascination lies in the changing nature of heritage audiences and their expectations – and what this should mean for the practice of interpretation. He has published three books: The Engaging Museum (2005), Transforming Museums in the 21st Century (2012), and Museums and the Challenge of Change (2021). Graham can be contacted at: black.rgraham@gmail.com.

To cite this article: Black, Graham (2023) ‘Rebuilding Lives: 50 years of Ugandan Asians in Leicester’ in Interpret Europe Newsletter 1-2023, pg. 15-16.

Available online: https://interpret-europe.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/PDF-Newsletter-2023_1-spring.pdf