Interpreters are advocates for audiences and not political activists – an appeal for our cultural sites to provide safe places for all visitors.

I am worried, and I suspect I’m not the only one. First of all, Brexit. Then the Covid crisis, which has thrown our sector into turmoil. But we have also seen developments in the cultural sector which are no less concerning. I mean political interference from, at least, two sides: government and political activism.

Against that background, sectors and professions like ours are faced with an unenviable, but all the more important, set of choices: What should be the role of museums, heritage sites and cultural venues today? Should we take the middle ground in any political, ideological, or moralistic movements? Or do we actively participate in the debates of the day, taking a particular position … become actors or even activists, influencers? And to what extent do we allow our sites to become activist spaces? Do we risk becoming propagandists? However, while these core questions are still unresolved, initiatives to “decolonise” museums, to remove statues and landmarks, to reorganise collections under political aspects, are happening with a distinct lack of transparency, scrutiny or debate within the sector.

So, what is the role of interpretation today? After all, it is us, in collaboration with the organisations we work for, who develop the narratives, produce the theme tables, select the content, write the panels, make the films, provide the experience. To highlight the problem we’re facing let’s look at the main questions in today’s discourse: climate change, diversity, racism, capitalism, globalism, and the heritage of colonialism. These are underpinned, of course, by the concept of intersectionality. The latter is an argumentative tool to prove the existence of injustice, discrimination and racism by examining the various elements that form the character of an individual or organisation. However, looking at it in a bit more detail and its practical application, it is also highly problematic: it means no less than using a foregone conclusion, an assumption, and then looking for evidence for its proof.

In its approach this turns traditional ideas of academic research and discussion on its head. De-duction instead of in-duction. Make a statement, state an opinion, then pick the evidence. And importantly: neglect, disregard, attack anything that does not fit the conclusion or sheds a slightly more varied light, adds another dimension, or two…

As an argumentative tool it allows us to argue almost anything, and in consequence, nothing: the earth is flat; mispronouncing a name is racism; the moon landing was faked; I won the election (Donald Trump); I won the World Cup (Gary Lineker’s response to Trump) …

This is an approach no different to religions or political ideologies, and a quite fundamental renouncement of centuries-old and hard fought-for ideas developed by the European Enlightenment. Using Western values as part of this strategy to question and in effect denying its cultural, political and scientific achievements; in human rights, in liberalism, in equality, democracy. The simplicity of the concept makes it so attractive and when it combines with human behaviours and developments in social media it makes for a toxic mix.

What to do? Firstly, as a leading principle, we are beholden to our audiences, and that means: all of our audiences. That means to represent them, to reflect their glorious variety, respect their multitude of views, in an inclusive manner. And that also includes politically. However, looking at ourselves, how representative of the population are we? Is there any political bias in the sector?

Recent developments seem to suggest so: the bewildering debate (or lack of?) around the translation of the poems of Amanda Gorman; the unquestioning support for the reorganisation of collections following a new, politically motivated orthodoxy; the lack of scrutiny surrounding the removal of historical statues in the UK; all this paints a fairly lop-sided picture.

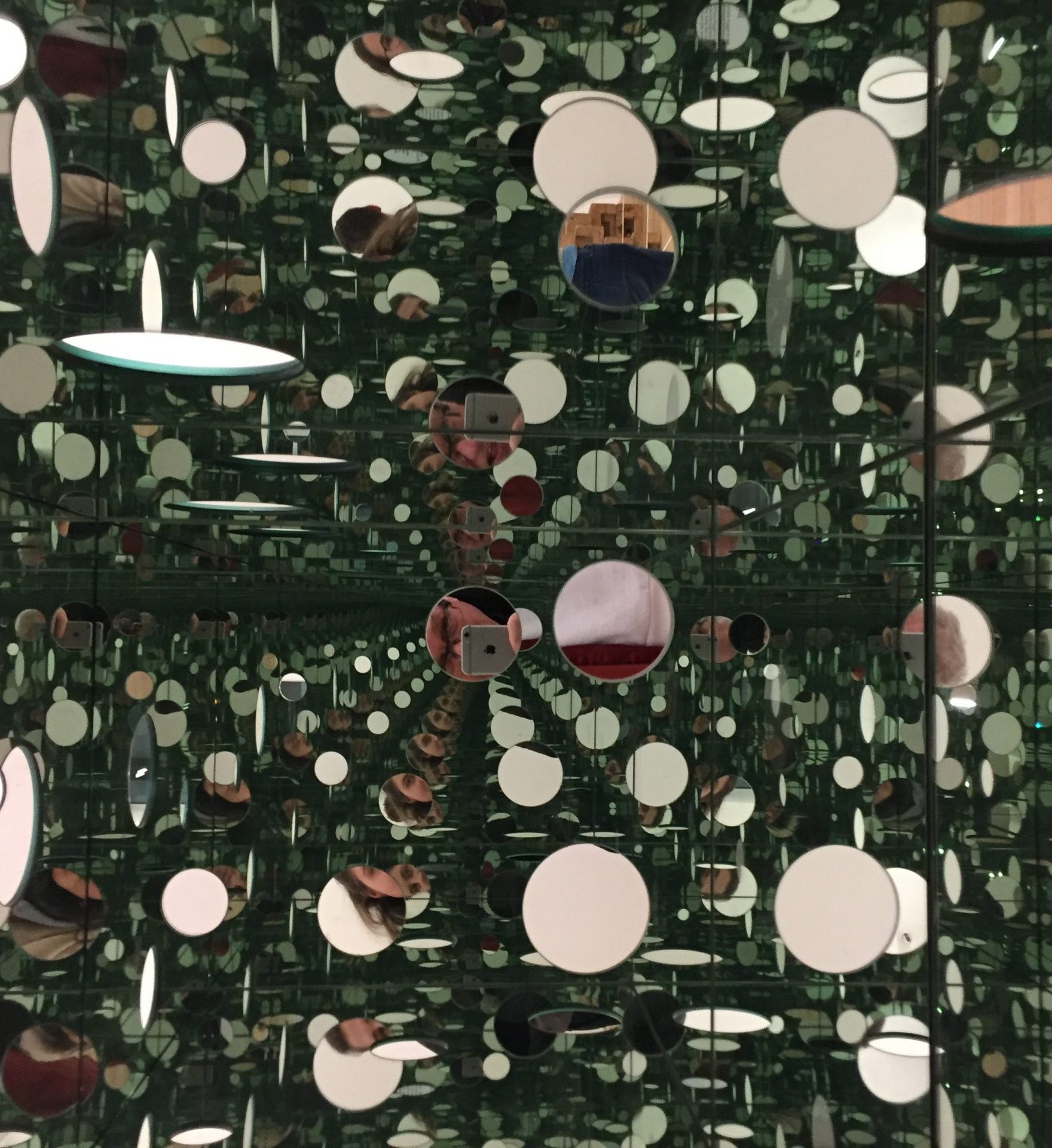

Secondly, racism. Much is made of Western (Caucasian?) racist attitudes being mainstream or dominant to the detriment of others, but this still begs the question: does it not exist in our other communities? What about African tribalism, Chinese attitudes to Westerners, Eastern Asians and Indians, Muslims and Jews, Hutus and Tutsis, the Yezedis, Shiites and Sunnites? Aren’t its roots rather a human condition, and the fear of the ‘other’ originally served as a survival mechanism, a protective measure against predators and competitors? We (should) have developed the capacity to overcome this instinct, through our intellectual potential, language, culture; but as history shows, this is true only to a degree. To truly overcome it, each of us have to take that long hard look in the mirror, as the saying goes.

Thirdly, starting with decolonisation, shouldn’t we be consistent and truly radical – and honest –, and lead the moral argument to its logical conclusion: shouldn’t we erase all traces of injustice, racism, sexism, oppression, exploitation, conquest, imperialism etc out of our collections? Let’s really put our money where our mouths are, and re-arrange our collections completely, according to our assessment of historical rights and wrongs. Obviously, this should and would have to involve not just Western collections, but everywhere in the world. Wars and conquest have happened throughout human history, across the world. Let’s be consistent, let’s set in motion a process of the complete redistribution of artefacts along the lines of historic justice.

But this is difficult. History, and framing it to suit one’s argument, can prove anything (and nothing). Treating history, and indeed culture, in such a way reduces it to a mere tool in a political dispute, and robs it of any intrinsic, let alone transcendental value. Doing so also leaves us caught in an endless circle, reliving, refighting past conflicts and arguments that in all likelihood do nothing to resolve today’s issues. On the contrary they will lead to disappointment and further fragmentation.

Unless their political purpose is clearly established and signposted, museums, heritage sites and cultural spaces should, in my opinion, not be places for political, ethical, social indoctrination or alignment; or follow whatever viewpoint their director, curator, interpreter stands for. Or be subject to the twin threats of government interference and politically motivated activist pressure. Particularly as a German, this makes me uncomfortable and feels like a move into the dangerous territory of political propaganda, however well-meaning and benign the original intentions. There is always the temptation to make value judgements based on our own political, ethical, moral views; to frame the argument from the outset (and “framing” has a double meaning as we all should be aware!); define a “corridor of opinion” – that fitting term for the current, intersectionalist model of cancelling out uncomfortable opinions that don’t fit the accepted discourse.

It might help to think back to the origin of our discipline, and to Freeman Tilden’s interpretive principles. (Obviously, there is abundant, further literature about the significance of sites, heritage, tangible and intangible culture and the role interpretation plays) His interpretive planning process might, should, still enable us to approach most sites, collections, country houses, etc with the cool, rational, organised and non-partisan mindset that is required, now more than ever:

- Possibly the most important point: we produce content for audiences. We are interpreters and use the interpretation planning process to make sure we do not create exhibits and displays for ourselves or our peer groups, but for “the public”. That includes diverging views on almost every topic. But it also means to be inclusive and not favour the interests of one group over another.

- We build our exhibitions on the prevalent themes of the individual site to make it sing to our visitors. That also implies we remain thematically, historically, narratively true and provide a storyline relevant to that particular site. Content that does not relate to the site, or only with much twisting and shoe-horning, has no place in that narrative.

- Tilden encourages us to take the holistic view, to include all relevant viewpoints, not just the ones which are convenient, “correct”, or expedient, or follow the accepted and acceptable discourse, the narrow “corridor of opinion”. This also includes historic views, language and terminology that are out-of-date (we don’t know how our views and language will be judged in future!).

- One of the key aims of the interpreter is that elusive element: revelation. However, this is a deeply personal experience. It will be different from visitor to visitor, and we have simply no right to impose, direct and lead that process according to our own wishes (‘lead’ as in ‘suggestive’). Our responsibility is to provide an environment that enables this process.

- Use induction instead of deduction, i.e. take the evidence to form our opinion, not your opinion to shape the evidence. Which obviously also means to accept contradictory facts and acknowledge them as they are. We should take a measured approach, step back, a bit like a referee that allows for the game to move on and just observe the rules are kept.

- A reminder: the 2010 Equality Act provides comprehensive protection in terms of the nine key characteristics, which include gender, religion, race. This means any discrimination under these characteristics is illegal but also vice versa, any preferential treatment. The name of the act emphasises its purpose: inclusion and equality. Any interpretation worth its salt will have taken this into account from the outset.

- I always found learning through stealth and enjoyment is much more effective than political lecturing and hectoring. In a confused and fragmented world, it will be helpful for visitors to enter a safe, protected and a tranquil space. And if there is no obvious learning outcome for some of our visitors: so be it, as long as they had a good time!

None of the above has anything to do with (political) indifference. We may have strongly held views on many topics, but how do we know if they are representative of any meaningful segment of the population rather than a vocal minority; or any more than a reaction to temporary issues?

Is it really in our right, role or responsibility to force discussions, and foist our views onto visitors who might come to our sites for other reasons than political, social or cultural education? To spell it out: in my definition of my role as an interpreter I do not see myself as an activist or a propagandist, rather as a referee or mediator; and reading Tilden I am sure this aligns more closely with what he had in mind for that special moment of revelation that should be the outcome for each visitor.

Also, in all of this, where is the sense of awe at a beautiful image, if we only look at its political background?; where the respect for the craftsmanship if we only think in ethical dimensions? History, culture and heritage are multi-dimensional. For me, we are losing the simple joy: the sense of amazement, of curiosity, of exploration and, speaking as a true German: humour. History and culture should be exciting and fun. The danger is that we are now on the way to creating very didactic, negative and joyless experiences. In German we have a word for this: ‘moralinsauer’

This moralising view is reductionist, the experience becomes one-dimensional, boring for many visitors and, in the worst case, annoying. Equally, the focus on guilt, shame and bad conscience is hardly a solid basis for our actions: we should be doing the right thing for the right reason not in order to avoid doing the wrong thing – or what is perceived, interpreted or suggested as such.

The latest reactions to the UK National Trust’s initiative show just that, the reverberations of a hastily incorporated and clumsily coordinated campaign for the sake of wokeness, has needlessly upset core (and paying) target audiences; rather than involving them and taking them on a shared journey.

Not all of us in the sector have the luxury to work politically or otherwise independent, but are under commercial remits and pressures. So, what then about our involvement in projects in the Middle East, in Central Asia, Russia, Africa? Attractive, lucrative, high-profile. But how do projects like these fit with our exacting standards on human rights, on equality, on democracy, on race, modern-day slavery, ecology and environment, ableism, ageism etc – which we’re at the same time happily and freely discussing at home. Brutally speaking, we have to question ourselves: how honest are we, when the standards that we are demanding from within the comfort and protection of our own four walls, within our own safe political systems, are not applied in quite the same way elsewhere, everywhere in the world? Doris Lessing touched on this in an interview in the Guardian in 2001, and I summarise that it is quite easy to be ethical when the circumstances are right and where it doesn’t hurt.

In conclusion, this is an appeal for museums, historic sites, country houses etc as safe spaces. They are, should remain, or even become, the best places to glance at human history, to wonder about human conflict, its stupidity, and the pointlessness of human strife. A place where we can mourn, marvel, consider and reflect. Accept that history is not fair. Where we can therefore, if we want, learn from it to help resolve today’s issues or at least see them from a different angle. And positively speaking to give us an opportunity to appreciate the light that culture can shine on the futility of human life.

What remains essential, in my view, to achieve this, is that we provide a calm and safe environment for all of our visitors, away from the fragmentation, disruption and politicisation that surrounds us. Our sites might be the only ones that are left for them.

Dirk Bennett, originally from Germany, has been in the UK since 1994. He holds an MA in history and archaeology and has worked in the cultural sector for private and public bodies. His projects have included the SS Great Britain, Battle Abbey and Dover Castle. Dirk is currently responsible for the City of London Corporation for the interpretation planning and delivery at Tower Bridge and The Monument. He writes extensively for publications in the UK and Germany as a freelance author and cultural correspondent.

The topic of this article will form the focus of June’s Thematic table. Why not join us online to share your own thoughts and experiences? Details can be found later in the newsletter.

To cite this article: Bennett, Dirk (2021) ‘Safe spaces for all’. In Interpret Europe Newsletter 1-2021, 4-7.

Available online: https://interpret-europe.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Newsletter-Spring-2021.pdf