Research summary of ‘It’s a Museum, But Not as We Know It: Issues for Local Residents Accessing the Museum of Old and New Art’, by Kate Booth and colleagues, published in Visitor Studies Journal (April 2017).

Accessibility to museums is the subject of lively debate in museology, not only in a physical context but also in terms of intellectual and cultural access. Heritage interpretation’s methods and means try to cater for all audiences. The article, ‘It’s a Museum, But Not as We Know It: Issues for Local Residents Accessing the Museum of Old and New Art’ (MONA), has shed a light on these issues, focusing on the MONA museum and art gallery in Tasmania.

The research provides insights into two important questions, a concern of many cultural institutions these days: does a non-traditional approach in museology have a positive and transforming effect on society and, in particular, how do local residents from disadvantaged social groups access an art gallery?

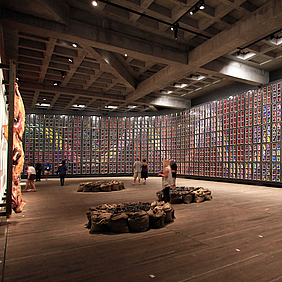

MONA obtained a flagship museum reputation for its ‘award winning architecture, a subterranean and cavernous layout, black internal walls, lack of labels, eclectic mix of antiquities and contemporary art, and interactive O-devices (iPods)’. It is claimed that unusual design and a non-pedagogical approach give every visitor an opportunity to engage with the content individually and that MONA intentionally avoids targeting any particular audience in order to attract all social groups. Therefore, the hypothesis was raised that the location is physically and intellectually accessible to everyone and that it ‘may contribute to local, cultural, social, and economic transformation’.

Even though MONA resides in a largely working-class area and offers free entry to locals, it receives mainly tourists, middle-class and highly educated visitors. The research, first using quantitative survey, showed that ‘socio-economic status, level of cultural capital and cultural engagement remain key factors in accessing MONA’. Similarly, those factors also influence visitors’ behaviour and attitude, namely ‘perceptions and engagement with culture’. Putting it differently, ‘those with time and resources for community engagement and those who are more aware of issues and developments in their local area’ are among the most common visitors.

In the second phase of the research, qualitative data were obtained through focus groups and one-to-one interviews with local community representatives. On one hand, many participants were reporting positive effects of visiting MONA. For example, they perceived it as entertaining and a meeting place, where they can participate in extraordinary and mind-broadening experiences, and meaningfully engage ‘with artwork, other people, or the architecture’.

However, there were many, especially those with less cultural capital, that found MONA hardly accessible. From a financial point of view, free entrance does not compensate otherwise high prices for food and drink. They also had concerns about the appropriateness of their children’s behaviour in a high-art institution and about some artistic content being inappropriate for children. The explicit nature of some art felt personally irrelevant to some participants. All these findings suggest that the institution is not equally accessible for everyone and thus cannot overcome social exclusivity.

In conclusion, the researchers question whether museums carry the potential of social and cultural change in the area. Even though MONA employs modern approaches for advanced visitor experiences and cultural accessibility and offers free entrance for locals, it remains inaccessible for many participants. Findings led researchers to the conclusion that no particular museology approach seems to fail, instead it appears that local community with their pre-set attitude and socio-economic patterns maintain ‘well-established patterns of exclusion’.

The article that was reviewed is:

Booth, K., O’Connor J., Franklin, A., Papastergiadis, N., (2017). It’s a Museum, But Not as We Know it: Issues for Local Residents Accessing the Museum of Old and New Art, Visitor Studies, 20:1, 10-32.

Helena Vičič from Slovenia is an IE Certified Interpretive Guide Trainer and heritage interpretation consultant. She studied interpretation at the University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI) in Scotland, UK. Helena volunteers as part of the IE Research Team, under which this review has been written. She can be contacted at: helena.vicic@gmail.com

To cite this article:

Vičič, Helena (2017) ‘Does the new museology approach cater for everybody?’. In Interpret Europe Newsletter 3-2017, 11-12.