At a soldier’s marching pace, it took four minutes to walk the 400m long corridors of the longest building in the world – the Royal Victoria Military Hospital, or Netley Hospital as it was known.

Built in 1856 at the request of Britain’s Queen Victoria after the Crimean War, it was the British Army’s first purpose-built military hospital, with a capacity for 1,000 patients. It was used extensively during WW1 during which around 50,000 patients were treated and the bed capacity was increased to 2,000 by building temporary Red Cross huts in the grounds. It then became a US General military hospital after mainland Europe was invaded in WW2.

The hospital design was heavily criticised by Florence Nightingale – England’s founder of modern nursing, who had trained nurses and organised the care of sick soldiers during the Crimean War in the 1850s – but ultimately it housed and cared for many wounded and dying service personnel who arrived by boat up the River Solent and had an easy short transfer to the wards.

The huge cemetery in the grounds of Royal Victoria Park is a stark and poignant reminder of the loss of life. Graves of German and Allied forces soldiers can be found there among the British, and it is also apparent that many children of the staff at the hospital fell victim to the conditions of the time and infectious diseases. The building itself was demolished in the 1960s and the central chapel is all that remains to tell the tale of the war wounded.

I visited recently and, so close to the centenary of the end of WW1, felt particularly moved by the interpretation of the space, which was delivered with Heritage Lottery Funding and opened last year. The chapel (with tea room – it’s always good to know where there is a good tea room!) and cemetery can be found within the 200 acres of Royal Victoria Country Park, managed by Hampshire County Council with open access to explore.

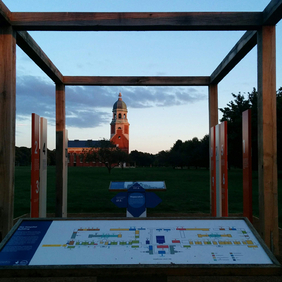

The dry ground – after an unusual British summer of no rain – reveals hints of the extent of the previous structure as the foundations of the missing walls appear in the parched brown grass. Now, a more permanent representation has been made as the corners of the once vast building have been subtly marked with open oak structures, providing a more visible cue and an aid to draw the eye along the sightline to the far end of the corridors. Each of the corners also houses a chapter in an interpretive story, revealing more about the soldiers, surgeons, nurses and families affected by the wars.

Translucent photographs provide an easy view into the past whilst still allowing you to see today’s landscape and the viewing tower provides great views over Southampton Water, one of the UK’s busiest shipping lanes, where you can imagine the wounded soldiers arriving by boat (although they later laid a railway line for improved access because the pier wasn’t long enough to cope with the tidal change in water level). But the interactive exhibition gallery inside the chapel is the most haunting where, with eyes closed, the ghostly voices transport you to the horrors of early 20th century medical care and the reality of war.

Particularly now, the story of this hospital – interpreted so sensitively and focussed on the human stories – spoke to me, and I hope will also speak to future generations of visitors.

Marie Banks is IE’s News Coordinator. She works as an interpretation consultant and copy writer/ editor and can be contacted at: marie@zebraproof.uk. [She has no relationship with Potter Associates who designed the interpretation and just thought it was a nice story to share.]

To cite this article:

Banks, Marie (2018) ‘Voices of the war wounded’. In Interpret Europe Newsletter 3-2018, 22.

Available online:

www.interpret-europe.net/fileadmin/Documents/publications/Newsletters/ie-newsletter_2018-3_autumn.pdf