Inspired by iecon25, some thoughts on the importance of non-formal education in historical memory and democratic citizenship.

Non-formal education plays a crucial role in lifelong learning, especially in the context of historical memory and democratic citizenship. The Council of Europe has been a fundamental actor in promoting cultural diversity, human rights, and peacebuilding since its creation in the aftermath of WW2. The European Cultural Convention of 1954 and the Faro Convention of 2005 are examples of efforts to safeguard and promote European cultural heritage, fostering mutual understanding and appreciation of cultural diversity.

The Faro Convention introduces a new way of considering cultural heritage, focusing on its value for local communities and their cultural identity. This convention highlights the importance of cultural heritage in sustainable socio-economic development and the promotion of democratic values, cultural diversity, and cultural identity. It recognises that cultural heritage is a resource for developing dialogue, democratic debate, and openness between cultures.

In the current context, with the political and societal challenges of the 21st century, the Council of Europe’s action in the field of culture and heritage focuses on promoting diversity and dialogue to cultivate a sense of identity, collective memory, and mutual understanding. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) has recognised the important role of museums as resources for human development and citizen engagement.

Since 1977, awards have been given to European museums that have demonstrated exemplary practices and stimulated innovation in the sector.

Education for democratic citizenship and human rights has always been a priority for the Council of Europe. This is why it has promoted the inclusion of sensitive and controversial parts of history in school curricula as it can reinforce democratic culture within a society and respect for different opinions, pluralism, tolerance, and diversity. However, we must be aware that delivering quality history education in schools can be challenging due to overloaded curricula, traditional teaching practices, and, in many instances, highly centralised education systems.

The Council of Europe has developed its work on Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights for decades, providing a model of competences for democratic culture. In 2016, the Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (RFCDC) was approved, including knowledge and critical understanding of oneself, society, and the world.

Nowadays, there is a necessity to put it into practice, and this requires for the member States a serious compromise in their educational systems, together with the implementation of the new initiative of the Council of Europe: The European Space for Citizenship Education, which seeks to reinforce democratic culture through education and remembrance.

Teaching history and memory is essential for understanding historical events constructively and openly, developing the competences needed for democratic citizenship. The inclusion of sensitive and controversial issues in history lessons enhances democratic culture, as the critical understanding of controversy facilitates respect for different opinions and promotes tolerance of ambiguity.

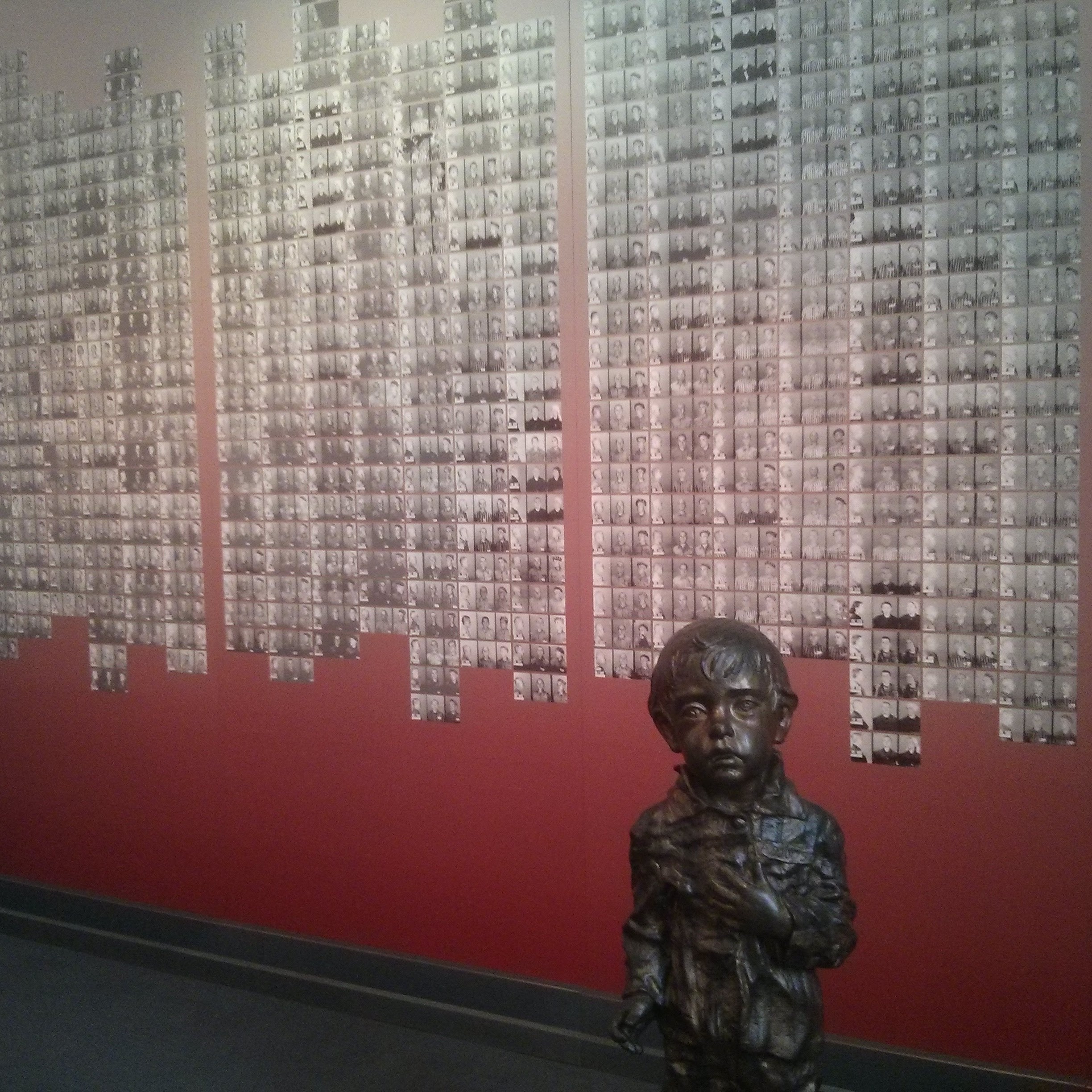

The world outside the classroom – whether real or virtual – can restore many victims of historical atrocities to historical significance and recognition and send powerful messages of inclusion and respect for diversity. Openness to cultural otherness and to other beliefs, world views and practices help young people to make sense of the world they live in. Therefore, it is highly recommended to bridge the gap between formal and non-formal education by ‘using’ remembrance sites, museums, cultural routes and promoting dialogue about history in Europe, establishing partnerships between research centres, public institutions, and non-governmental organisations to commemorate sensitive historical events networks.

There can be many views and interpretations of the same historical events and there is validity in a multi-perspective approach that assists and encourages students to respect diversity and cultural difference, instead of conventional history teaching.

This is the case with the understanding and interpretation of heroes and villains in history. In Spain, contemporary history has been marked by the coup d’état of 1936, the Civil War, and Franco’s dictatorship for 40 years. Franco, the dictator, was a villain for the people who were killed, for the political prisoners, for the millions of citizens who did not enjoy liberty, for those who hardly had social and civil rights, for the losers. On the contrary, for the winners, Franco was seen as a hero, a vision that goes on. Even nowadays his death is commemorated every year by his followers, the extreme right and very conservative political groups. The arrival of democracy in 1975 was a milestone in the country’s history. This year is the 50th anniversary of his death and, funnily enough, his death is commemorated by the defenders of democracy and by the ones who don’t believe in democracy.

In 2006, an educational reform was approved that included the subject of Education for Citizenship and Human Rights, aiming to promote self-esteem, personal dignity, freedom, and responsibility. However, in 2013, this subject was suppressed as a full school subject. In 2014, the UN Rapporteur urged the extension of recognition and coverage of reparation programmes, highlighting the need to consolidate efforts in historical and human rights education. Memory and tools for the interpretation of the past require legislation to guarantee the inclusion of these topics in school curricula and restore dignity to the victims.

The 2022 Spanish Democratic Memory Law focuses on the recovery, safeguarding, and dissemination of Spain’s democratic memory, promoting knowledge of Spanish democratic history and the struggle for democratic freedoms. Memory sites play an important role as physical materialisations of the past, helping to rationalise and soothe the emotions and memories of survivors and victims.

In conclusion, the teaching of history and its relevance for democratic citizenship education are fundamental for strengthening democratic values, combating authoritarianism, and promoting social cohesion. History should be taught in a way that fosters critical thinking and addresses multiple perspectives, allowing students to understand the complexity of the past and its relevance to the present. This is a key issue, considering the evolution and extension of ideologies that are against shared values that we have built as a European society for decades.

The organisations that were born after the horrors of WW2, such as the Council of Europe, are compromised with the defence of human rights. We must never forget that those atrocities that happened in the past due to totalitarian regimes started with hate speeches, violation of human rights, racism, intolerance… the same atmosphere as is dangerously spread all over Europe by extreme groups.

Therefore, Education for Democratic Citizenship should be a compulsory subject at all stages of formal education and form part of vocational training and non-formal education. It is more important than ever before. Democracy cannot be taken for granted, as we saw in the past, and we see now.

Luz Martínez Seijo is a Member of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe and a Member of the Spanish Congress. She delivered a keynote at iecon25 in Poland on this topic.

To cite this article: Seijo, Martínez Luz (2025) ‘Interpreting heroes and villains in history‘ in Interpret Europe Newsletter 1-2025, pg. 4-5.

Available online: PDF Newsletter Spring 2025