Interpreting climate change means understanding people’s worldviews – and maybe even starting by expanding our own.

Have you ever played catch with a hyperobject? It is like playing chess on a pitch-black night or reading a book whose pages randomly reorder like the walls in Maze Runner. Yet interpreters often toss these hyperobjects to their audiences only to find that some visitors cannot play.

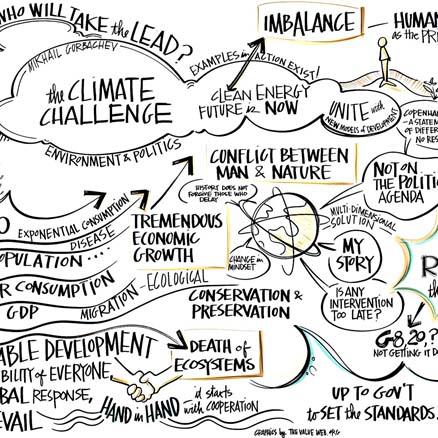

According to philosopher Timothy Morton, a hyperobject is something so wicked, so massively distributed across time and space, that it totters on the unknowable. Consider the greatest hyperobject: Climate change stretches across millions of years. It interacts with weather, biology, soils, oceans, and cascades across the Earth: clouds, rainfall, glaciers, permafrost, and forests. Rising storms, new diseases, floods, droughts, and heat waves dare plants and animals to adapt or die. The beastly phenomenon accelerates changes in technology, politics, economy, culture, and spirituality. These causes, feedbacks, tipping points, delays, and overshoots provoke heated conversations about human adaptation, mitigation, transformation, or business-as-usual.

But when one corn farmer peers skyward, she senses a completely different world than that of a Chinese businessman who looks down from the 100th floor of a skyscraper, or a child who trips in a flooded playground of an inner-city school, or a climate scientist who fine-tunes a climate model.

What these people see influences what policies they support, actions they will take, and the future they expect for their children.

Interpreters modify climate change interpretation according to worldview

We intuitively realise that people understand differently: newborns can perceive only inner desires for food, warmth, and mother; as they grow, they learn to distinguish hands from environment, feelings from those of everyone else. Eventually they realise that when a puppet disappears behind the door, it still exists.

A child’s self-identity grows to include not just family, but friends, then larger groups, such as race, religion, and nationality. Children think at first only in concrete terms and later abstractly. And this process doesn’t stop at adulthood—people continue to grow their meaning-making, using more complex reasoning, across larger swaths of space and time.

They can, however, plateau. Some adults think childishly. Others continue to develop their entire lives, cultivating higher powers of awareness, mind, and empathy. Developmental psychologists have researched this unfolding worldview pathway.

But if people operate from different worldviews, and interpreters present climate change in terms that audiences don’t comprehend, then messages fly over heads. For example, climate scientists spew information about long-term trends, feedbacks, delays, and tipping points that grant us only 12 years to reverse course — and many people recoil. These scientists think that if only people understood basic climate science, then rising consciousness would save us all. But people’s climate change perceptions mix political ideology, values, emotions, and the very way they sense climate change. If only it were simply a lack of information.

The STAGES Model applied to climate change

Gail Hochachka used the STAGES Model, a developmental psychology model, in which she studied why and how people make climate change meaning in different ways. Understanding this, interpreters should better communicate complex environmental issues like climate change. Gail asked Salvadorans what climate change meant to them, and people took photos to explain their answers. She and STAGES developer Dr. Terri O’Fallon then analysed the captioned photos with a validated scoring assessment to determine underlying worldviews.

How different audiences understand climate change

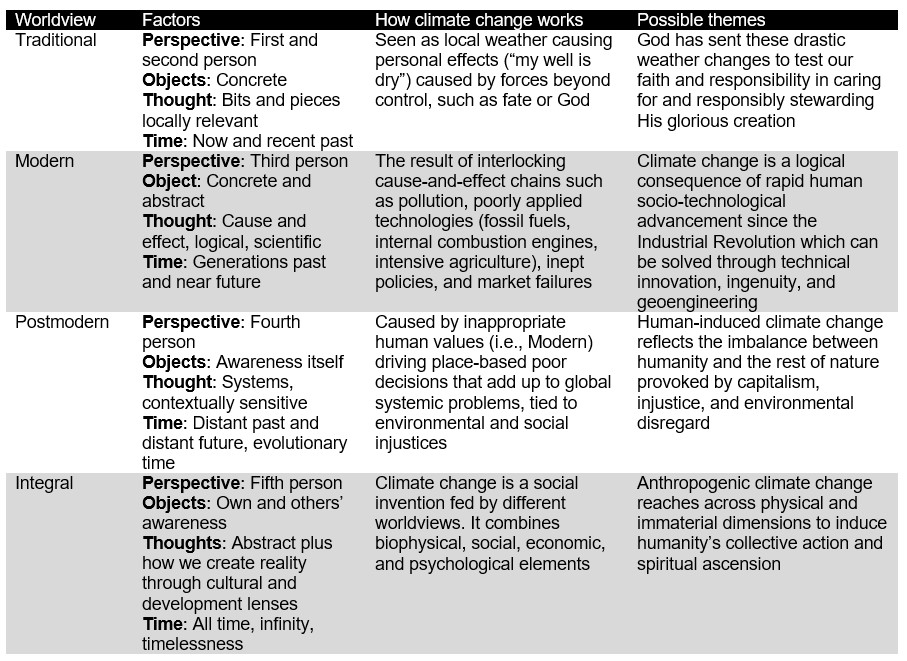

Psychologists, philosophers, and researchers have mapped these worldviews. I only illustrate the most prominent four today. Their conflicting values account for most clashes in newspapers.

STAGES shows that people vary across worldviews according to four key factors.

Perspectives

First person: People see only through their own eyes.

Second person: People see through the eyes of others.

Third person: People see objectively to navigate between multiple perspectives, necessary for rational, scientific thinking.

Fourth person: People recognise the role of context in constructing meaning.

Fifth person: People view the constructed nature of all reality.

Object Awareness

People can be aware of only concrete objects (rain, river, weather change), abstract objects (precipitation rate, climate change, idea of democracy), or be aware of their own awareness; that is, they are aware or conscious of what they perceive and how they think.

Thought Complexity

Thought starts with fragmented bits and pieces and continues to more mechanistic and logical cause-and-effect. More complex thinking implies understanding that realities are contextual, systemic, and change across local differences. Finally, some people also see how different values and worldviews influence the systems and objects they perceive and create.

Time

Starting with children who do not live in time (only in the present moment), the next stage is perception of the present with limited past, and then future. As development increases, the scale widens to distant past and future and then finally the entire evolutionary span from the Big Bang to eternity and timelessness.

The table shows how worldviews construct climate change. Remember as we move up, people see more of the hyperobject and can contemplate facets that previous worldviews don’t even know exist.

What interpreters do with this

When interpreters understand diverse climate change realities, they can better transcend name-calling, fighting, and frustration, and can instead connect with various ways that people make meaning. This builds on capacities that interpreters already wield, translating meaning into different stories, values, and metaphors. As Sam Ham says, “audience is everything.”

Interpreters that grow their own awareness can work with more audiences. Interpreters can develop themselves by reading and discussing other points of view, considering how context influences issues, learning about how climate change meanings vary, and studying each worldview’s landscape.

The more eyes you see through, then, the more concrete objects begin to reveal abstract angles, the more time extends backward and forward, the more walls recede and ceilings rise, leaving you in a larger room to comprehend. Wise interpreters see people building realities from fragments and flashes of the grand climate change hyperobject, and interpret accordingly.

This newsletter article was adapted from a longer discussion on Jon’s blog: https://jonkohl.medium.com/interpreting-climate-change-means-understanding-peoples-worldviews-5a0a244b1518

Author bio

Founding director of the PUP Global Heritage Consortium, an international non-profit that applies a holistic focus to heritage management and conservation, Jon is also an interpretation trainer, planner, and freelance writer with two books on interpretation. See his publications at ResearchGate

Jon has been invited to host an IE webinar on this topic soon so keep an eye on the website for the date announcement and do join us to continue the discussion and add your own thoughts and experiences.

References

Hochachka, G., 2019. On matryoshkas and meaning-making: Understanding the plasticity of climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 57, 101917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.05.001

Morton, T., 2013. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology After the End of the World. Posthumanities, Minneapolis

Salzer, Jeff. (November 2019). Video interview with Gail Hochacka and Terri O’Fallon. The Daily Evolver. www.dailyevolver.com/2019/11/climate-changes-at-every-stage/

To cite this article: Kohl, Jon (2021) ‘Have you ever played catch with a hyperobject?’ in Interpret Europe Newsletter 3-2021, 4-6.

Available online: https://interpret-europe.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Newsletter-Autumn-2021.pdf